African-American History: Selections for Younger Readers

Maya Angelou once stated,

Love recognizes no barriers. It jumps hurdles, leaps fences, penetrates walls to arrive at its destination full of hope.

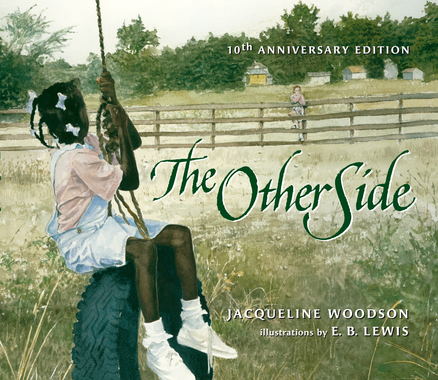

Clover, a black girl, and Annie, a white girl, are separated by a simple fence. The fence separates the black side of town from the white, but it symbolizes a far greater barrier than that made of wood.

Passing each other in town, sneaking glances, and wondering why a simple harmless game of jump rope cannot be enjoyed by both girls because of a fence is puzzling to each of them. The larger issue hangs in the air unspoken. A simple solution and compromise of fence sitting by both girls breaches the gulf, and slowly allows the natural trust of children to emerge, sharing the bond of friendship and play. Regardless of skin color, hope, common sense, and humanity reign in the heart of a child when Annie states, “Someday somebody’s going to come along and knock this old fence down.” And her friend Clover agrees, “Someday.”

Change is an inevitable certainty in life, yet sometime it comes ever so slowly and in oh-so-small increments, too small to see in a single day. But come it does. Aside from its beautiful watercolor paintings, the book relates a story with a powerful punch. It reminded me of the song from the musical South Pacific, “You’ve Got to Be Taught,” written by Rodgers and Hammerstein. Prejudice is a learned lesson and just as easily can be changed; one child at a time. It’s that simple, or maybe that complex.

It is sometimes said that truth is stranger than fiction and in this book, January’s Sparrow, which is alternately painful and awe-inspiring, it reaffirms the idea that self-determination and ultimately freedom are rights to be valued by all people, regardless of race, since they are dearly bought.

It is sometimes said that truth is stranger than fiction and in this book, January’s Sparrow, which is alternately painful and awe-inspiring, it reaffirms the idea that self-determination and ultimately freedom are rights to be valued by all people, regardless of race, since they are dearly bought.

It chronicles the flight from slavery in Kentucky to freedom in Michigan at great personal risk to the Crosswhite family. Research by Mary McCafferty Douglas provides the framework for Patricia Polacco’s personal interest in this subject. The author lives twelve miles from Marshall, Michigan, the setting of the story, and her home was an inn and safe house for the Underground Railroad.

Sadie, the heroine of our story, and her family’s flight from the plantation on which they live is precipitated by the cruel beating and presumed death of January, a family friend whose flight to freedom is thwarted by the plantation master, Frances Giltner. January is also Sadie’s closest friend, and an artist who has carved a beautiful wooden sparrow for her—a most precious possession. Realizing their sons are next to be taken, Sadie’s parents flee with their children, aided by the Underground Railroad, a unique network of people helping slaves reach free states, and with the help of this railroad they arrive in Marshall, Michigan, a free state. Unfortunately, in this flight Sadie forgets the hand-carved wooden sparrow given to her by the runaway slave January, who is presumed dead. Although Michigan is a free state, it is still against the law of the land to aid runaway slaves, who may still be caught and returned to their owners.

Life falls into a comfortable, easy pattern filled with school, jobs, and Sadie’s first glimpse of a snowfall. Frances, a new baby sister, is born, and everyone is astonished that she is named for the plantation master. Sadie’s mom says with a quick response when Sadie asks why, “So’s none of you will ever fear that name again,” spoken with great wisdom. Watching hogs being auctioned, Sadie confides to her new white friend Polly that such a thing can happen to people, and has! Not only can they be bid on, but babies can be pulled from mothers’ arms and sold. Sadie confesses she and her family are runaway slaves themselves.

The family is discovered by the former slave owner’s son, whom Sadie’s mom nursed as a baby, and the town must make a moral decision. It hangs in the balance for a slight second until a shirtless young black man with scarred, striped skin from a horrific lashing, tells the crowd “this is what will happen to them.” It is January, the carver of Sadie’s wooden sparrow—alive! The slave trackers are jailed for three days as Polly’s father, with whom she has shared Sadie’s secret, allows them to flee to Canada. January’s death, it is revealed, had been faked, and he carefully carried the wooden sparrow to return it to Sadie and the only family he had known.

Polacco’s book provides the arc of the saga of the Crosswhite family from slavery in Kentucky to freedom in Marshall, Michigan. The journey is complete as an aged and free Sadie burns the wooden sparrow given to her by January, the beloved friend and fellow freedom seeker, as she says, “It’s fixin’ to fly…and so am I.”

A great picture book puts you into the story, draws you into the experience of the characters, and makes you care what they are feeling and ultimately what happens to them.

Ms. Polocco succeeds brilliantly!