African-American History: Selections for Older Readers

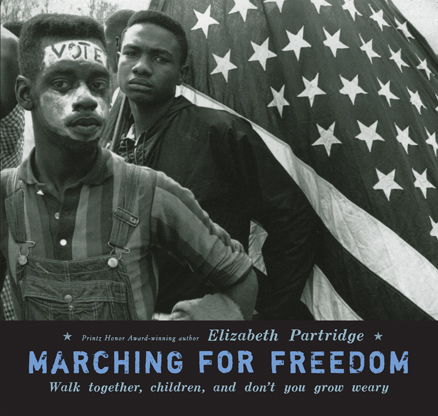

Marching for Freedom is an acclaimed work of non-fiction for Young Readers, winning the 2010 Boston Globe-Horn Book Award for Excellence in Children’s Literature, Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Young Adult Literature and the Jane Addams Children’s Book Award.

The title of Mrs. Partridge’s book is taken from an African American spiritual often quoted by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The outrage voiced by Amelia Boynton, a northern black woman appalled at how black people were treated in the South is evident in her 1960s quote “A vote-less people is a hopeless people.” Although the population of Selma, Alabama was half black, 99% of the voters were white. Not one black person had registered to vote in 65 years! Unreasonable tests about the Constitution and a poll tax, plus accumulated taxes based on years when one had not voted, made voting impossible for many poor citizens. Mrs. Boynton asked Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for their assistance with the motivation, money, and media attention that was needed to begin a change, and change did begin—slowly.

The stage, Dr. King reasoned, was set for a dramatic protest movement. A speech by Dr. King on January 2, 1965, 102 years after Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation freeing the slaves, set in motion the beginning of freedom to vote for the black population. Sparked by the death on February 19 of a young protester called Jimmie Lee Jackson, preacher James Bevel was anxious to highlight this senseless violence, calling on his congregation to march to Montgomery. The fire of a momentous idea took shape. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. presided at Jimmie Lee Jackson’s funeral, he announced a march from Selma to Montgomery on March 7! Highlights of that historic march were marked by Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, when Alabama state troopers met the marchers. As one marcher stated, “We were going to get killed or get free.” Clubs, followed with clouds of tear-gas, and chaos ensued as mounted horses moved into the crowd. The book’s black-and-white photos emphasize the stark life and death moral black and white issue at stake in the five-day march, filled with the indelible faces and words of these then children who marched and related their experiences movingly as adults in this book.

Their memories and words are intact, raw, and riveting. Some pictures sear into one’s vision. A young crew cut black man, Bobby Simmons, the four letters “VOTE” standing in relief against the sunscreen slathered on his forehead. Montgomery and the goal of the Capitol building is reached on March 25,1965, with Rosa Parks speaking briefly, and finally Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. When the speech is over, 30,000 people joined hands, swayed and sang “We Shall Overcome.” On August 1, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act in Washington outlawing literacy tests and polling taxes, appointing federal registrars ensuring all qualified citizens were at last free to register to vote. Of the many that marched, hundreds of students and young people put themselves at risk for a principle. Sometimes here, as in life, example is the strongest teacher. Their daring defiance encouraged adults to follow suit.

Perhaps Dr. King expressed it best when he said in his speech to the city of Selma,

“How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

“And a child shall lead them” seems an apt phrase to describe this evocative book, depicting powerfully dark days yet an ultimately triumphant chapter in American history.

Can a potent form of sugar spit (sounds yucky, right?), baked into conjured bread by an elderly slave named Bett, speed up, slow down, or even reverse time? It is a strong yet quickly dissipating charm only children have, and grown-ups lose. Had I known that, I could have used it to good advantage earlier in life. Too late now, Liz!

Jeffrey Kluger has written a totally engrossing book of Lillie, a young slave girl living on Greenfog Plantation with an unrelenting dream of freedom for her family. Much like Mattie in the book True Grit, there is a moral imperative driving Lillie’s actions headlong and heedless of her own safety in order to clear her father’s name and thus secure her family’s freedom.

The thrust of the story, driven by the desire of Lillie’s father to take advantage of the promise extended to slaves, including wives and children, secures freedom for a family in exchange for the slave’s participation in the Civil War on the side of the Confederacy. This agreement remains valid should the slave die in battle. It is a compelling quid pro quo drawing the reader in immediately. Though her father is killed at the Battle of Vicksburg and found with a bag of Yankee gold coins on his person, Lillie is wholly confident in her father’s innocence and outraged that the accusation of thievery negates the agreed upon freedom for herself, her mother, and Plato, her younger brother.

The imminent sale of Plato as a cabin boy is the trigger for Lillie to risk time reversal with chilling risk involved, both for her and Cato, a friend who agrees to accompany her on her amazing journey. Lillie’s defiance echoes in the words “That’s the stone truth and no one’s gonna hold my family nor sell my brother on account of a lie.” A bargain formed with Henry, a free slave present at her father’s death, precipitates an exchange of favors. In return for informing his family at a nearby plantation of his safety, Henry will see Lillie’s handwritten letter, a rarity for a young slave girl, delivered to the one white man who can attest to her father’s honesty, the elusive Mr. Appleton. Images of the horrors of war, the inhuman treatment, cruelty, and daily unrelenting fear of life as a slave are drawn with exquisite and frightening emotional reality. Will Lillie and Cato’s time reversal journey, facilitated by the kindly conjurer Bett, reveal the truth for Lillie? A joyful reunion with her father amid the smoke and smell of death are vividly drawn in Lillie and Cato’s sudden appearance at the battle scene at Vicksburg.

Can the improbable and unimaginable occur—can Lillie’s father rejoin his family and events, like time, be reversed? Her father imparts a fateful lesson to Lillie in their final moments together as he says wisely, “If I’m supposed to get took by a bullet, I’ll get took by a bullet. If I ain’t, I ain’t.” Jeffrey Kluger conjures his own spell of a fascinating tale of one black family’s journey to freedom, facilitated by magic and the strong moral center of a young girl.

As a side note, a partially sympathetic portrait of the tentative friendship existing between Lillie and Sarabeth, the slave master’s daughter, reveals loyalty to one’s family and their welfare, however misguided in the actions of Sarabeth, can run equally strong in both communities—one slave and one free. Final images remain fixed in the reader’s mind: the drawstring bag containing the conjuring black firestone coupled with the puzzled look of the new slave baker as she peers into Bett’s oven with one brick missing —the maker of magic.

Will Lillie and Cato return to Greenfog Plantation with the information to clear her father and free them? Can time reversal alter the past? In the midst of a slave population breeding fear and distrust, can shared good fortune provide the ability to purchase freedom for others as well?

Jeffrey Kluger answers all of these questions and, in the process, ties all unanswered questions together in a bittersweet yet ultimately satisfying coda, leaving the reader with a feeling of hope for Lillie and her family and the resilience of the human heart.