Is Common Sense “Gone With the Wind” Too?

Well, here we go! Another over-reaction to something that makes very little sense to me. In the wake of the call to remove the Confederate flag from the South Carolina State House and “consign it to museums” in the wake of the brutal murders at the Emanual African Methodist Episcopal Church, comes a call for showings of “Gone With the Wind” to be consigned to a museum-only display of the movie, based on Margaret Mitchell’s sweeping novel of the South.

Critic Lou Lumenick says in his article, “…what does it say about us as a nation if we continue to embrace a movie that, in the final analysis, stands for many of the same things as the Confederate flag that flutters so dramatically over the dead and wounded soldiers at the Atlanta train station…?”

What does it say about us as a nation if we begin to censor and marginalize freedom of choice in what we read and view? And who decides to decide?

Apparently many voted to disagree with Mr. Lumenick’s critique, as its suggestion sent people flocking in droves to store up copies of the movie, boosting sales of GWTW to record levels. On Friday morning of last week, “Gone With the Wind” was the overall best-selling Blu-ray feature film on Amazon’s US website.

Though Mr. Lumenick did not call for an outright ban of the movie at multiplexes, he did feel its showing should be relegated to museums. I disagree.

Who can forget the intensity of this historic film with actress Hattie McDaniel, as its emotional center, as Mammy, for which she so rightly won an Academy Award for her performance in 1939; the first black actress to do so.

How does this relate to the picture book and its exposure to possible censorship?

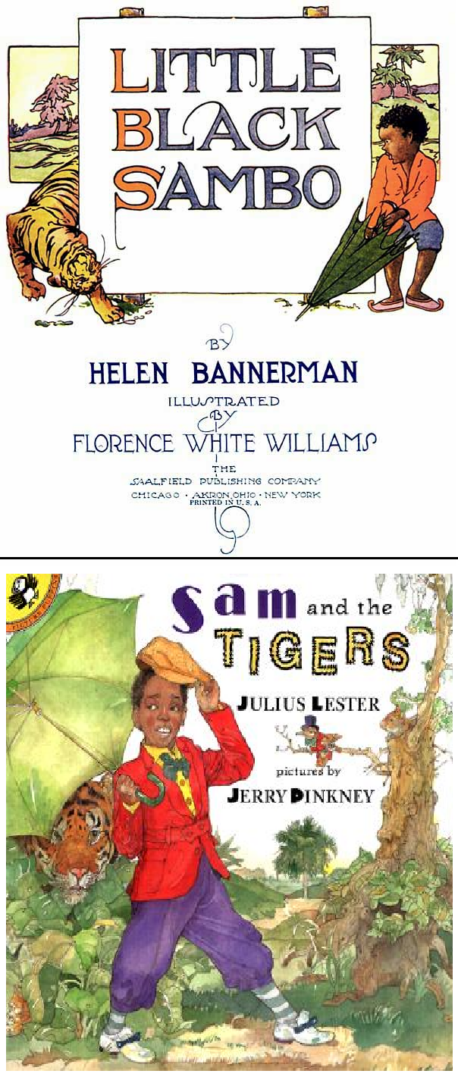

In 2014, I wrote a post at The Snuggery on the children’s picture book called “The Story of Little Black Sambo.”

In 1899, Helen Bannerman wrote a picture book by that title. In the original Sambo is pictured as a South Indian. It was termed insensitive and, in a way, stereotypical of races with art that exaggerated African facial features.

In 1996, Julius Lester and Jerry Pinckney did a reimagined version of Ms. Bannerman’s book and called it, “Sam and the Tigers.” It was considered by many to be more sensitive and less divisive than the original. I encouraged readers to read both in my post, and trust themselves to make a determination for their children themselves.

Between the two versions is not only the lapse of time, but in the more recent telling is a fresh and modern approach that is more aware of cultural awakenings to things that might appear divisive or insensitive in the 1899 picture book.

But here’s the amazing thing: Mr. Pinckney never hints at racist intent in Ms. Bannerman’s picture book. In fact, both Mr. Pinckney and Mr. Lester, who are both African American, regarded Sambo as a hero when they read the book as children. It was HOW he was depicted, that “took away his hero status.” That, and the fact that since the 17th century the term “Sambo” had a racially negative connotation.

Waylaid by tigers and commandeered out of his clothing, shoes and umbrella, Sambo ultimately triumphs by his wits, as he collects the tigers’ residue left behind as they chase each other around a tree at warp speed, and melt in the process.

The tigers are everyday bullies and they are defeated by the smarts of Sambo as he redirects their attempts to devour him as he proffers his clothing as décor for their ears, feet and tails! And the tigers wind up in a fray among one another as to which is “the fairest”, so to speak! Mr. Lester also uses the voice of “southern black storytelling” in “Sam and the Tigers” to great success.

Jerry Lester said for years many people avoided the picture book of “The Story of Little Black Sambo” for fear of being called racist. But something this “African American picture book” author said stuck with me as I read “Sam and the Tigers”…“Yet what other story had I read at age seven and remembered for fifty years?” Like many of my readers, I came to Ms. Bannerman’s book as child, and the second book, as an adult.

In the end, it is the heroic and imaginative world that children enter into, that created Ms. Bannerman’s book and the Lester/Pinckney version; both versions of which I encourage you to read and see for yourselves.

Classic picture books, and movies, last because they stand the test of the great leveler, and that is something called time.

Let audiences be the judge of whether “Gone With the Wind” is in that class, not the critic. And if people vote with their pocketbooks at times, given the enormous sale of this movie since Mr. Lumenick’s critique, I think the vote is in.

Very wise. I can recall exactly the first time I read Bannerman’s tale, sitting on the front porch of a cousin’s house. I was so impressed with how smart that kid was in the story. Would I have thought of that plan to save my life? Probably, not. But, it prompted me to think about what I might do. Critical thinking—-what a concept!